A hard lesson for me over the past several years of my career has been figuring out how to pick my battles. I’ve seen many friends and colleagues struggle with this as well: how do you know when to involve yourself in something, and how do you know when to stay out of it? How do you figure out where the line is?

The setup

If you’re reading this looking for advice, you’re probably a go-getter. You consider yourself a responsible person, who cares deeply about doing things right. Your care may be focused on software and systems, or on people and organizations, or on processes and policies, or all of the above.

This attitude has probably served you well in your career, especially those of you who have been working for a number of years. You’ve been described as having a “strong sense of ownership,” and people admire your ability to think broadly about problems. You try to think about the whole system around a problem, and that helps you come up with robust solutions that address the real challenges and not just the symptoms.

And yet, despite these strengths, you’re often frustrated. You see so many problems, and when you identify those problems, people sometimes get mad. They don’t take your feedback well. They don’t want to let you help fix the situation. Your peers rebuff you, your manager doesn’t listen to you, your manager’s manager nods sympathetically and then proceeds to do nothing about it.

That kind of grinding frustration can wear you down over time. I know, because I’ve been there. I left a cushy big company job because I saw too many things I felt powerless to fix. When I got into management, I figured that I would have the power to make things right. Then I thought that when I became the leader of all of engineering I could do it. Then I thought that when I became an executive I would be able to do it. Chasing that dream of being able to fix all the things contributed to me feeling exhausted, and dare I say a bit burned out, when I finally decided to leave my CTO gig.

Escaping the Trap

I’ve come to realize that there isn’t a job where you can fix all the things. It is true that founders have immense ability to set direction and culture, but trying to control everything happening in a company causes many other problems that are outside of the scope of this essay. Assuming that you are not a founder, you should just take a minute to really let it sink in: there is no place you can go where you can control everything and fix all the problems, no matter how much you get promoted. There’s always going to be something you can’t fix.

So how do you decide where to exert your energy?

Step one: Figure out who owns this problem

If it’s your job (or the job of someone who reports to you), great. Go to it! Tend your own garden first. Make systems that are as robust as you believe systems should be. Follow processes that you believe are effective and efficient. If you are not leading by example, you have to start there. Stop reading now and go fix the things!

If there’s no clear owner, do you know why? Is it just because no one has gotten around to doing it, or has the organization specifically decided not to do it? If no one’s gotten around to doing it, can you do it yourself? Can your org do it, just within your org?

If it’s someone else’s job, how much does it affect your day to day life? Does it bother you because they’re doing it wrong, or does it actually, really, significantly make it harder for you to do your job? Really? That significantly? There’s no work around at all? If it is not directly affecting your job, drop it!

Step two: Talk to all the people

If you don’t clearly own the problem, you need to talk to people. If you feel tired by the idea of talking to all people, stop! This is a sign that you should not pick this battle! It’s already draining you and you haven’t even started on the path to addressing it. It is probably a good idea to just try to let it go, or at best, tell your manager that you worried about whatever it is, and then let it go.

If you’re ok with talking to all the people, then get out there and get a sense of the problem beyond you and your team. You can do this formally, with a document that you prepare addressing the problem as you see it, or informally, as a series of user interviews. You will need this information to make a case to fix it, and to make a plan for how to fix it. Does the information you’ve gathered from others make you think that perhaps this problem really isn’t as important as you first thought it was? Is someone else already solving this problem? Great! Let it go!

If you know who should own this, you need to give them a chance to fix it. Which means you need to come with examples of how the problem is impacting you or your team. Missing those examples? Stop! This is not your problem to fix! Don’t go bringing problems based on people from other teams complaining to you. Those teams need to bring up the problems themselves. If you must, tell their manager that you’re hearing these complaints, and let that manager decide whether to deal with it.

Step three: Plan the fix

Ok so you talked to all the people and the problem is still not fixed. Assuming no one owns the problem and you really still want to own it and fix it, great. Make a concrete plan for how you will fix it, and share that plan with the people who need to know about it. You should expect that you will need to get feedback and revise your plan, and the amount of feedback and revision required will be directly related to how big the problem is, how many people it impacts, and how controversial the fix you’re proposing is. Expect this feedback, buy-in, and revision process to take a while. You’ll need feedback from all corners, friends are good to start with but be sure to include your skeptics too. Your goal is to convince everyone that they want you to solve the problem. Yes, that means a lot more talking. If you’re tired now, maybe this isn’t your problem to solve!

If this problem is with another team, and you talked to that team, brought them clear examples of why it is truly a big deal, and they haven’t answered your concerns to your satisfaction, you have a choice. Do you escalate to your manager? If you have clear examples of why it’s a problem, and your peer hasn’t been able to do anything, this is a perfectly fine time to escalate! Consider though whether you can negotiate a fix with the other team, or work around the other team. And, especially when the problem is cultural, consider whether you really need to make this problem into a big deal, or whether you can just let it go.

Step four: Enact the plan

And now we get to the tricky part. You saw this problem, you complained about it, you made it your own, and now you have to fix it! This is what you wanted, right?

Unfortunately, the fix will almost certainly take a lot longer than you’re thinking it will take, and it will probably be a lot of work on your part to see it all the way through. And by the way, it’s unlikely that you get to give up any of your other problems to take this one on. But this is something you feel passionately about, and that should make the extra work worth it to you.

Step five: Think about how many of these you can actually do

Good job! You fixed the problem! It was probably a little bit harder to fix than you expected huh? Especially if it was a cultural thing that you needed to change. But it should feel good to have it fixed. You can see the improvement you were aiming for, and you’ve got a great story to tell.

Take a moment to reflect on whether it was worth the effort to you, and think about how many more things like this you see at the company you’re in that you really want to change just as much as that one.

Think about what else you could be doing with that extra energy. Finishing a critical project sooner? Hiring a few people who are more in tune with your way of doing things, who might be able to fix things for you? Writing a novel? Getting a personal best on your deadlift?

Pick Your Culture First and Foremost

Learning how to pick your battles is also about learning how to pick your company and pick your boss, because your job really shouldn’t be all or even mostly about battles. Going through this exercise of solving an unowned problem is fun once in a while, but it’s a real drag when you feel like you’re surrounded by such problems, you can’t ignore them, and you’re powerless to fix them. That is a good sign that it’s time to find a new job, preferably somewhere that is more in tune with your way of doing things. Life is so much more fun when you have people around you that you trust to solve problems, even the problems you have a lot of opinions about.

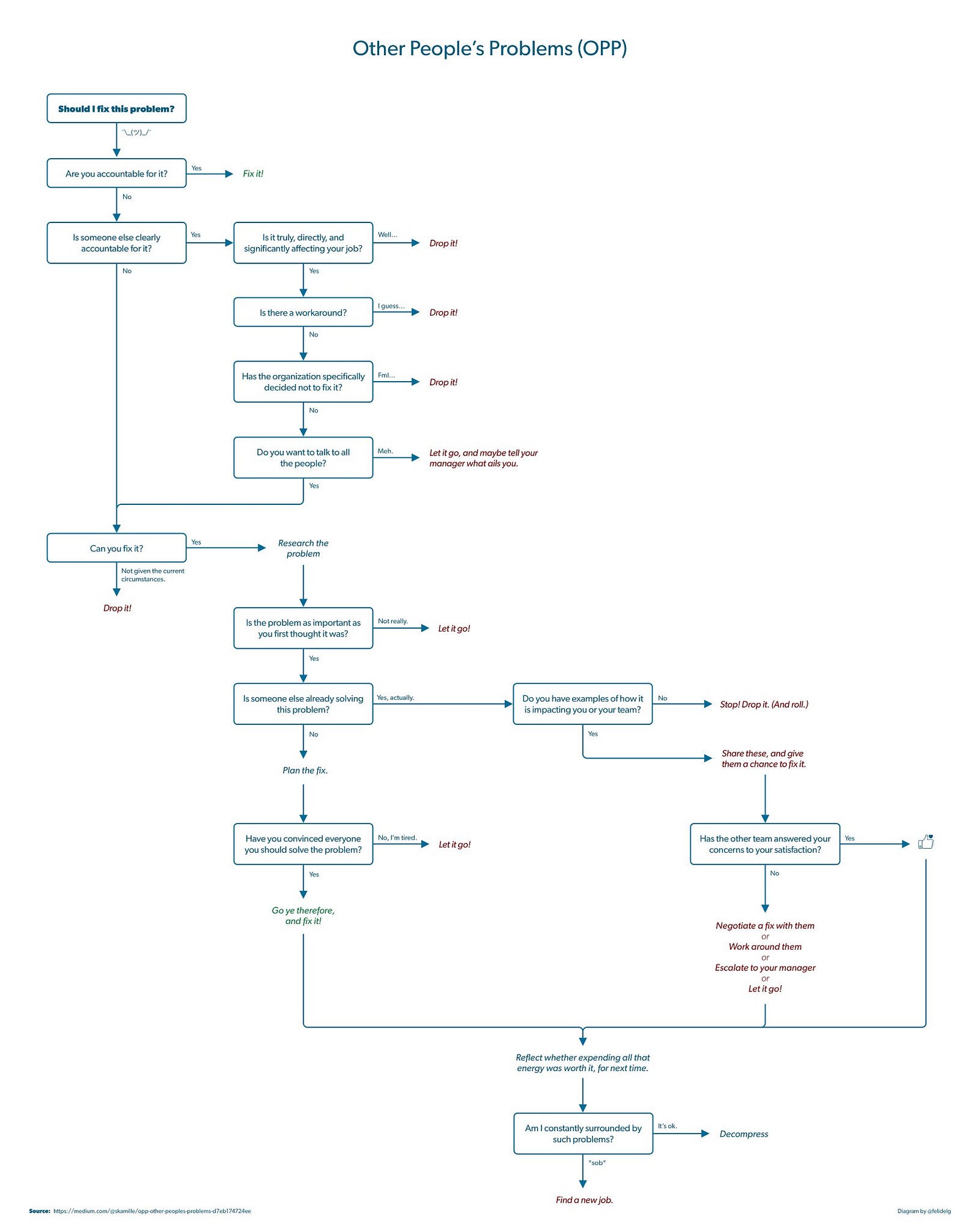

|

| Flowchart courtesy twitter user https://twitter.com/felidelg |

Enjoy this post? You might like my book, The Manager’s Path, available on Amazon and Safari Online!